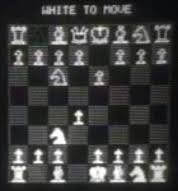

Mac Hack IV, a 1967 chess software built by Richard Greenblatt, gained notoriety for being the first computer chess program to engage in a chess tournament and to play adequately against humans, obtaining a USCF rating of 1,400 to 1,500.

Greenblatt's software, written in the macro assembly language MIDAS, operated on a DEC PDP-6 computer with a clock speed of 200 kilohertz.

While a graduate student at MIT's Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, he built the software as part of Project MAC.

"Chess is the drosophila [fruit fly] of artificial intelligence," according to Russian mathematician Alexander Kronrod, the field's chosen experimental organ ism (Quoted in McCarthy 1990, 227).

Creating a champion chess software has been a cherished goal in artificial intelligence since 1950, when Claude Shan ley first described chess play as a task for computer programmers.

Chess and games in general involve difficult but well-defined issues with well-defined rules and objectives.

Chess has long been seen as a prime illustration of human-like intelligence.

Chess is a well-defined example of human decision-making in which movements must be chosen with a specific purpose in mind, with limited knowledge and uncertainty about the result.

The processing capability of computers in the mid-1960s severely restricted the depth to which a chess move and its alternative answers could be studied since the number of different configurations rises exponentially with each consecutive reply.

The greatest human players have been proven to examine a small number of moves in greater detail rather than a large number of moves in lower depth.

Greenblatt aimed to recreate the methods used by good players to locate significant game tree branches.

He created Mac Hack to reduce the number of nodes analyzed while choosing moves by using a minimax search of the game tree along with alpha-beta pruning and heuristic components.

In this regard, Mac Hack's style of play was more human-like than that of more current chess computers (such as Deep Thought and Deep Blue), which use the sheer force of high processing rates to study tens of millions of branches of the game tree before making moves.

In a contest hosted by MIT mathematician Seymour Papert in 1967, Mac Hack defeated MIT philosopher Hubert Dreyfus and gained substantial renown among artificial intelligence researchers.

The RAND Corporation published a mimeographed version of Dreyfus's paper, Alchemy and Artificial Intelligence, in 1965, which criticized artificial intelligence researchers' claims and aspirations.

Dreyfus claimed that no computer could ever acquire intelligence since human reason and intelligence are not totally rule-bound, and hence a computer's data processing could not imitate or represent human cognition.

In a part of the paper titled "Signs of Stagnation," Dreyfus highlighted attempts to construct chess-playing computers, among his many critiques of AI.

Mac Hack's victory against Dreyfus was first seen as vindication by the AI community.

You may also want to read more about Artificial Intelligence here.

See also:

Alchemy and Artificial Intelligence; Deep Blue.

Further Reading:

Crevier, Daniel. 1993. AI: The Tumultuous History of the Search for Artificial Intelligence. New York: Basic Books.

Greenblatt, Richard D., Donald E. Eastlake III, and Stephen D. Crocker. 1967. “The Greenblatt Chess Program.” In AFIPS ’67: Proceedings of the November 14–16, 1967, Fall Joint Computer Conference, 801–10. Washington, DC: Thomson Book Company.

Marsland, T. Anthony. 1990. “A Short History of Computer Chess.” In Computers, Chess, and Cognition, edited by T. Anthony Marsland and Jonathan Schaeffer, 3–7. New York: Springer-Verlag.

McCarthy, John. 1990. “Chess as the Drosophila of AI.” In Computers, Chess, and Cognition, edited by T. Anthony Marsland and Jonathan Schaeffer, 227–37. New York: Springer-Verlag.

McCorduck, Pamela. 1979. Machines Who Think: A Personal Inquiry into the History and Prospects of Artificial Intelligence. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.