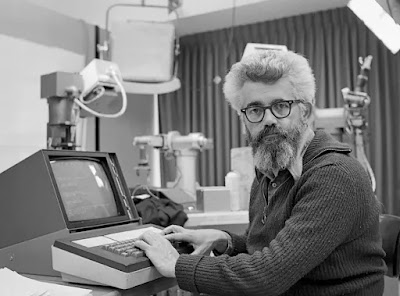

John McCarthy (1927–2011) was an American computer scientist and mathematician who was best known for helping to develop the subject of artificial intelligence in the late 1950s and pushing the use of formal logic in AI research.

McCarthy was a creative thinker who earned multiple

accolades for his contributions to programming languages and operating systems

research.

Throughout McCarthy's life, however, artificial intelligence

and "formalizing common sense" remained his primary research interest

(McCarthy 1990).

As a graduate student, McCarthy first met the concepts that

would lead him to AI at the Hixon conference on "Cerebral Mechanisms in

Behavior" in 1948.

The symposium was place at the California Institute of

Technology, where McCarthy had just finished his undergraduate studies and was

now enrolled in a graduate mathematics program.

In the United States, machine intelligence had become a

subject of substantial academic interest under the wide term of cybernetics by

1948, and many renowned cyberneticists, notably Princeton mathematician John

von Neumann, were in attendance at the symposium.

McCarthy moved to Princeton's mathematics department a year

later, when he discussed some early ideas inspired by the symposium with von

Neumann.

McCarthy never published the work, despite von Neumann's

urging, since he believed cybernetics could not solve his problems concerning

human knowing.

McCarthy finished a PhD on partial differential equations at

Princeton.

He stayed at Princeton as an instructor after graduating in

1951, and in the summer of 1952, he had the chance to work at Bell Labs with

cyberneticist and inventor of information theory Claude Shannon, whom he

persuaded to collaborate on an edited collection of writings on machine

intelligence.

Automata Studies received contributions from a variety of

fields, ranging from pure mathematics to neuroscience.

McCarthy, on the other hand, felt that the published studies

did not devote enough attention to the important subject of how to develop

intelligent machines.

McCarthy joined the mathematics department at Stanford in

1953, but was fired two years later, maybe because he spent too much time

thinking about intelligent computers and not enough time working on his

mathematical studies, he speculated.

In 1955, he accepted a position at Dartmouth, just as IBM

was preparing to establish the New England Computation Center at MIT.

The New England Computation Center gave Dartmouth access to

an IBM computer that was installed at MIT and made accessible to a group of New

England colleges.

McCarthy met IBM researcher Nathaniel Rochester via the IBM

initiative, and he recruited McCarthy to IBM in the summer of 1955 to work with

his research group.

McCarthy persuaded Rochester of the need for more research

on machine intelligence, and he submitted a proposal to the Rockefeller

Foundation for a "Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence"

with Rochester, Shannon, and Marvin Minsky, a graduate student at Princeton,

which included the first known use of the phrase "artificial

intelligence." Despite the fact that the Dartmouth Project is usually

regarded as a watershed moment in the development of AI, the conference did not

go as McCarthy had envisioned.

The Rockefeller Foundation supported the proposal at half

the proposed budget since it was for such an unique field of research with a

relatively young professor as author, and because Shannon's reputation carried

substantial weight with the Foundation.

Furthermore, since the event took place over many weeks in

the summer of 1955, only a handful of the guests were able to attend the whole

period.

As a consequence, the Dartmouth conference was a fluid

affair with an ever-changing and unpredictably diverse guest list.

Despite its chaotic implementation, the meeting was crucial

in establishing AI as a distinct area of research.

McCarthy won a Sloan grant to spend a year at MIT, closer to

IBM's New England Computation Center, while still at Dartmouth in 1957.

McCarthy was given a post in the Electrical Engineering

department at MIT in 1958, which he accepted.

Later, he was joined by Minsky, who worked in the

mathematics department.

McCarthy and Minsky suggested the construction of an

official AI laboratory to Jerome Wiesner, head of MIT's Research Laboratory of

Electronics, in 1958.

McCarthy and Minsky agreed on the condition that Wiesner let

six freshly accepted graduate students into the laboratory, and the

"artificial intelligence project" started teaching its first

generation of students.

McCarthy released his first article on artificial

intelligence in the same year.

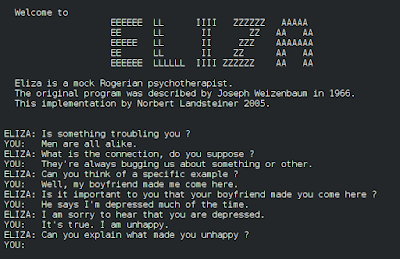

In his book "Programs with Common Sense," he described

a computer system he named the Advice Taker that would be capable of accepting

and understanding instructions in ordinary natural language from nonexpert

users.

McCarthy would later define Advice Taker as the start of a

study program aimed at "formalizing common sense." McCarthy felt that

everyday common sense notions, such as comprehending that if you don't know a

phone number, you'll need to look it up before calling, might be written as

mathematical equations and fed into a computer, enabling the machine to come to

the same conclusions as humans.

Such formalization of common knowledge, McCarthy felt, was

the key to artificial intelligence.

McCarthy's presentation, which was presented at the United

Kingdom's National Physical Laboratory's "Symposium on Mechansation of

Thought Processes," helped establish the symbolic program of AI research.

McCarthy's research was focused on AI by the late 1950s,

although he was also involved in a range of other computing-related topics.

In 1957, he was assigned to a group of the Association for

Computing Machinery charged with developing the ALGOL programming language,

which would go on to become the de facto language for academic research for the

next several decades.

He created the LISP programming language for AI research in

1958, and its successors are widely used in business and academia today.

McCarthy contributed to computer operating system research

via the construction of time sharing systems, in addition to his work on

programming languages.

Early computers were large and costly, and they could only

be operated by one person at a time.

McCarthy identified the necessity for several users

throughout a major institution, such as a university or hospital, to be able to

use the organization's computer systems concurrently via computer terminals in

their offices from his first interaction with computers in 1955 at IBM.

McCarthy pushed for study on similar systems at MIT, serving

on a university committee that looked into the issue and ultimately assisting

in the development of MIT's Compatible Time-Sharing System (CTSS).

Although McCarthy left MIT before the CTSS work was

completed, his advocacy with J.C.R.

Licklider, future office head at the Advanced Research

Projects Agency, the predecessor to DARPA, while a consultant at Bolt Beranek

and Newman in Cambridge, was instrumental in helping MIT secure significant

federal support for computing research.

McCarthy was recruited to join what would become the second

department of computer science in the United States, after Purdue's, by

Stanford Professor George Forsythe in 1962.

McCarthy insisted on going only as a full professor, which

he believed would be too much for Forsythe to handle as a young researcher.

Forsythe was able to persuade Stanford to grant McCarthy a

full chair, and he moved to Stanford in 1965 to establish the Stanford AI

laboratory.

Until his retirement in 2000, McCarthy oversaw research at

Stanford on AI topics such as robotics, expert systems, and chess.

McCarthy was up in a family where both parents were ardent

members of the Communist Party, and he had a lifetime interest in Russian

events.

He maintained numerous professional relationships with

Soviet cybernetics and AI experts, traveling and lecturing there in the

mid-1960s, and even arranged a chess match between a Stanford chess computer

and a Russian equivalent in 1965, which the Russian program won.

He developed many foundational concepts in symbolic AI

theory while at Stanford, such as circumscription, which expresses the idea

that a computer must be allowed to make reasonable assumptions about problems

presented to it; otherwise, even simple scenarios would have to be specified in

such exacting logical detail that the task would be all but impossible.

McCarthy's accomplishments have been acknowledged with

various prizes, including the 1971 Turing Award, the 1988 Kyoto Prize,

admission into the National Academy of Sciences in 1989, the 1990 Presidential

Medal of Science, and the 2003 Benjamin Franklin Medal.

McCarthy was a brilliant thinker who continuously imagined

new technologies, such as a space elevator for economically transporting stuff

into orbit and a system of carts strung from wires to better urban

transportation.

In a 2008 interview, McCarthy was asked what he felt the

most significant topics in computing now were, and he answered without

hesitation, "Formalizing common sense," the same endeavor that had

inspired him from the start.

Find Jai on Twitter | LinkedIn | Instagram

You may also want to read more about Artificial Intelligence here.

See also:

Cybernetics and AI; Expert Systems; Symbolic Logic.

References & Further Reading:

Hayes, Patrick J., and Leora Morgenstern. 2007. “On John McCarthy’s 80th Birthday, in Honor of His Contributions.” AI Magazine 28, no. 4 (Winter): 93–102.

McCarthy, John. 1990. Formalizing Common Sense: Papers, edited by Vladimir Lifschitz. Norwood, NJ: Albex.

Morgenstern, Leora, and Sheila A. McIlraith. 2011. “John McCarthy’s Legacy.” Artificial Intelligence 175, no. 1 (January): 1–24.

Nilsson, Nils J. 2012. “John McCarthy: A Biographical Memoir.” Biographical Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences. http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/mccarthy-john.pdf.