Predictive policing is a term that refers to proactive

police techniques that are based on software program projections, particularly

on high-risk areas and periods.

Since the late 2000s, these tactics have been progressively

used in the United States and in a number of other nations throughout the

globe.

Predictive policing has sparked heated debates about its

legality and effectiveness.

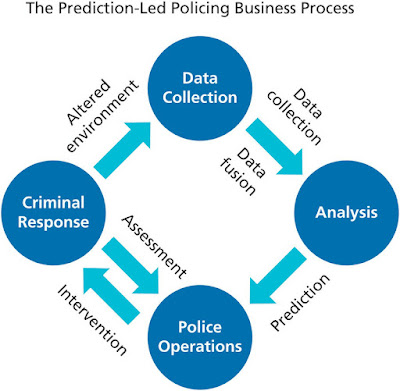

Deterrence work in policing has always depended on some type

of prediction.

Furthermore, from its inception in the late 1800s,

criminology has included the study of trends in criminal behavior and the

prediction of at-risk persons.

As early as the late 1920s, predictions were used in the

criminal justice system.

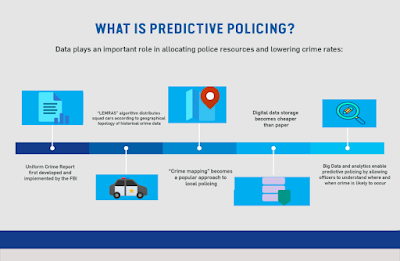

Since the 1970s, an increased focus on geographical

components of crime research, particularly spatial and environmental

characteristics (such as street lighting and weather), has helped to establish

crime mapping as a useful police tool.

Since the 1980s, proactive policing techniques have

progressively used "hot-spot policing," which focuses police

resources (particularly patrols) in regions where crime is most prevalent.

Predictive policing is sometimes misunderstood to mean that

it prevents crime before it happens, as in the science fiction film Minority

Report (2002).

Unlike conventional crime analysis approaches, they depend

on predictive modeling algorithms powered by software programs that

statistically analyze police data and/or apply machine-learning algorithms.

(1) locations and times when crime is more likely to occur;

(2) persons who are more likely to conduct crimes; and

(3) the names of offenders and victims of crimes.

"Predictive policing," on the other hand,

generally relates mainly to the first and second categories of predictions.

Two forms of modeling are available in predictive policing

software tools.

The geospatial ones show when and where crimes are likely to

occur (in which area or even block), and they lead to the mapping of crime

"hot spots." Individual-based modeling is the second form of

modeling.

Variables like age, criminal histories, gang involvement, or

the chance of a person being engaged in a criminal activity, particularly a

violent one, are used in programs that give this sort of modeling.

These forecasts are often made in conjunction with the

adoption of proactive police measures (Ridgeway 2013).

Police patrols and restrictions in crime "hot

areas" are naturally included in geospatial modeling.

Individuals having a high risk of becoming involved in

criminal behavior are placed under observation or reported to the authorities

in the case of individual-based modeling.

Since the late 2000s, police agencies have been

progressively using software tools from technology businesses that assist them

create projections and implement predictive policing methods.

With the deployment of PredPol in 2011, the Santa Cruz

Police Department became the first in the United States to employ such a

strategy.

More than sixty police agencies throughout the United States

already employ PredPol.

In 2012, the New Orleans Police Department was one of the

first to employ Palantir to perform predictive policing.

Since then, many more software programs have been created,

including CrimeScan, which analyzes seasonal and weekday trends in addition to

crime statistics, and Hunchlab, which employs machine learning techniques and

adds weather patterns.

Some police agencies utilize software tools that enable

individual-based modeling in addition to geographic modeling.

The Chicago Police Department, for example, has relied on

the Strategic Subject List (SSL) since 2013, which is generated by an algorithm

that assesses the likelihood of persons being engaged in a shooting as either

perpetrators or victims.

Individuals with the highest risk ratings are referred to

the police for preventative action.

Predictive policing has been used in countries other than

the United States.

PredPol was originally used in the United Kingdom in the

early 2010s, and the Crime Anticipation System, which was first utilized in

Amsterdam, was made accessible to all Dutch police departments in May 2017.

Several concerns have been raised about the accuracy of

predictions produced by software algorithms employed in predictive policing.

Some argue that software systems are more objective than

human crime data analyzers and can anticipate where crime will occur more

accurately.

Predictive policing, from this viewpoint, may lead to a more

efficient allocation of police resources (particularly police patrols) and is

cost-effective, especially when software is used instead of paying human crime

data analysts.

On the contrary, opponents argue that software program

forecasts embed systemic biases since they depend on police data that is itself

heavily skewed due to two sorts of faults.

To begin with, crime records appropriately represent law

enforcement efforts rather than criminal activity.

Arrests for marijuana possession, for example, provide

information on the communities and people targeted by police in their anti-drug

efforts.

Second, not all victims report crimes to the police, and not

all crimes are documented in the same way.

Sexual crimes, child abuse, and domestic violence, for example, are generally underreported, and U.S. citizens are more likely than non-U.S. citizens to report a crime.

For all of these reasons, some argue that predictions

produced by predictive police software algorithms may merely tend to repeat

prior policing behaviors, resulting in a feedback loop: In areas where the

programs foresee greater criminal activity, policing may be more active,

resulting in more arrests.

To put it another way, predictive police software tools may

be better at predicting future policing than future criminal activity.

Furthermore, others argue that predictive police forecasts

are racially prejudiced, given how historical policing has been far from

colorblind.

Furthermore, since race and location of residency in the

United States are intimately linked, the use of predictive policing may

increase racial prejudices against nonwhite communities.

However, evaluating the effectiveness of predictive policing

is difficult since it creates a number of methodological difficulties.

In fact, there is no statistical proof that it has a more

beneficial impact on public safety than previous or other police approaches.

Finally, others argue that predictive policing is

unsuccessful at decreasing crime since police patrols just dispense with

criminal activity.

Predictive policing has sparked several debates.

The constitutionality of predictive policy's implicit

preemptive action, for example, has been questioned since the hot-spot policing

that commonly comes with it may include stop-and-frisks or unjustified

stopping, searching, and questioning of persons.

Predictive policing raises ethical concerns about how it may

infringe on civil freedoms, particularly the legal notion of presumption of

innocence.

In reality, those on lists like the SSL should be allowed to

protest their inclusion.

Furthermore, police agencies' lack of openness about how

they use their data has been attacked, as has software firms' lack of

transparency surrounding their algorithms and predictive models.

Because of this lack of openness, individuals are oblivious

to why they are on lists like the SSL or why their area is often monitored.

Members of civil rights groups are becoming more concerned

about the use of predictive policing technologies.

Predictive Policing Today: A Shared Statement of Civil

Rights Concerns was published in 2016 by a coalition of seventeen

organizations, highlighting the technology's racial biases, lack of

transparency, and other serious flaws that lead to injustice, particularly for

people of color and nonwhite neighborhoods.

In June 2017, four journalists sued the Chicago Police

Department under the Freedom of Details Act, demanding that the department

provide all information on the algorithm used to create the SSL.

While police departments are increasingly implementing

software programs that predict crime, their use may decline in the future due

to their mixed results in terms of public safety.

Two police agencies in the United Kingdom (Kent) and

Louisiana (New Orleans) have terminated their contracts with predictive

policing software businesses in 2018.

Find Jai on Twitter | LinkedIn | Instagram

You may also want to read more about Artificial Intelligence here.

See also:

Clinical Decision Support Systems; Computer-Assisted Diagnosis.

References & Further Reading:

Collins, Francis S., and Harold Varmus. 2015. “A New Initiative on Precision Medicine.” New England Journal of Medicine 372, no. 2 (February 26): 793–95.

Haskins, Julia. 2018. “Wanted: 1 Million People to Help Transform Precision Medicine: All of Us Program Open for Enrollment.” Nation’s Health 48, no. 5 (July 2018): 1–16.

Madara, James L. 2016 “AMA Statement on Precision Medicine Initiative.” February 25, 2016. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association.

Morrison, S. M. 2019. “Precision Medicine.” Lister Hill National Center for Biomedical Communications. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services.