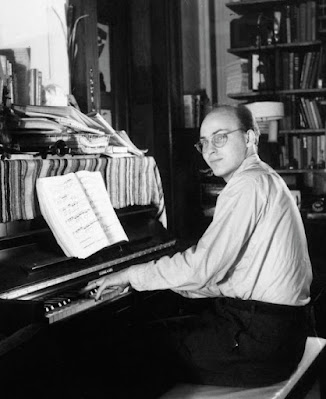

Donner Professor of Natural Sciences Marvin Minsky (1927–2016) was a well-known cognitive scientist, inventor, and artificial intelligence researcher from the United States.

At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he cofounded

the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory in the 1950s and the Media Lab in the

1980s.

His renown was such that the sleeping astronaut Dr.

Victor Kaminski (killed by the HAL 9000 sentient computer)

was named after him when he was an adviser on Stanley Kubrick's iconic film

2001: A Space Odyssey in the 1960s.

At the conclusion of high school in the 1940s, Minsky got

interested in intelligence, thinking, and learning machines.

He was interested in neurology, physics, music, and

psychology as a Harvard student.

On problem-solving and learning ideas, he collaborated with cognitive psychologist George Miller, and on perception and brain modeling theories with J.C.R. Licklider, professor of psychoacoustics and later father of the internet.

Minsky started thinking about mental ideas while at Harvard.

"I thought the brain was made up of tiny relays called

neurons, each of which had a probability linked to it that determined whether

the neuron would conduct an electric pulse," he later recalled.

"Technically, this system is now known as a stochastic

neural network" (Bern stein 1981).

This hypothesis is comparable to Donald Hebb's Hebbian

theory, which he laid forth in his book The Organization of Behavior (1946).

In the mathematics department, he finished his undergraduate

thesis on topology.

Minsky studied mathematics as a graduate student at

Princeton University, but he became increasingly interested in attempting to

build artificial neurons out of vacuum tubes like those described in Warren

McCulloch and Walter Pitts' famous 1943 paper "A Logical Calculus of the

Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity." He thought that a machine like this

might navigate mazes like a rat.

In the summer of 1951, he and fellow Princeton student Dean

Edmonds created the system, termed SNARC (Stochastic Neural-Analog Reinforcement

Calculator), with money from the Office of Naval Research.

There were 300 tubes in the machine, as well as multiple

electric motors and clutches.

Making it a learning machine, the machine employed the

clutches to adjust its own knobs.

The electric rat initially walked at random, but after

learning how to make better choices and accomplish a wanted objective via

reinforcement of probability, it learnt how to make better choices and achieve

a desired goal.

Multiple rats finally gathered in the labyrinth and learnt

from one another.

Minsky built a second memory for his hard-wired neural

network in his dissertation thesis, which helped the rat recall what stimulus

it had received.

When confronted with a new circumstance, this enabled the

system to explore its memories and forecast the optimum course of action.

Minsky had believed that by adding enough memory loops to

his self-organizing random networks, conscious intelligence would arise

spontaneously.

In 1954, Minsky finished his dissertation, "Neural Nets

and the Brain Model Problem." After graduating from Princeton, Minsky

continued to consider how to create artificial intelligence.

In 1956, he organized and participated in the DartmouthSummer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence with John McCarthy,

Nathaniel Rochester, and Claude Shannon.

The Dartmouth workshop is often referred to as a watershed

moment in AI research.

Minsky started replicating the computational process of

proving Euclid's geometric theorems using bits of paper during the summer

workshop since no computer was available.

He realized he could create an imagined computer that would

locate proofs without having to tell it precisely what it needed to accomplish.

Minsky showed the results to Nathaniel Rochester, who

returned to IBM and asked Herbert Gelernter, a new physics hire, to write a

geometry-proving program on a computer.

Gelernter built a program in FORTRAN List Processing

Language, a language he invented.

Later, John McCarthy combined Gelernter's language with

ideas from mathematician Alonzo Church to develop LISP, the most widely used AI

language (List-Processing).

Minsky began his studies at MIT in 1957.

He started worked on pattern recognition difficulties with

Oliver Selfridge at the university's Lincoln Laboratory.

The next year, he was hired as an assistant professor in the

mathematics department.

He founded the AI Group with McCarthy, who had transferred

to MIT from Dartmouth.

They continued to work on machine learning concepts.

Minsky started working with mathematician Seymour Papert in

the 1960s.

Perceptrons: An Introduction to Computational Geometry

(1969) was a joint publication describing a kind of artificial neural network

described by Cornell Aeronautical Lab oratory psychologist Frank Rosenblatt.

The book sparked a decades-long debate in the AI field,

which continues to this day in certain aspects.

The mathematical arguments provided in Minsky and Papert's

book pushed the field to shift toward symbolic AI (also known as "Good

Old-Fashioned AI" or GOFAI) in the 1980s, when artificial intelligence

researchers rediscovered perceptrons and neural networks.

Time-shared computers were more widely accessible on the MIT

campus in the 1960s, and Minsky started working with students on machine

intelligence issues.

One of the first efforts was to teach computers how to solve

problems in basic calculus using symbolic manipulation techniques such as

differentiation and integration.

In 1961, his student James Robert Slagle built a software

for symbol manipulation.

SAINT was the name of the application, which operated on an

IBM 7090 transistorized mainframe computer (Symbolic Automatic INTegrator).

Other students applied the technique to any symbol

manipulation that their software MACSYMA would demand.

Minsky's pupils also had to deal with the challenge of

educating a computer to reason by analogy.

Minsky's team also worked on issues related to computational

linguistics, computer vision, and robotics.

Daniel Bobrow, one of his pupils, taught a computer how to

answer word problems, an accomplishment that combined language processing and

mathematics.

Henry Ernst, a student, designed the first

computer-controlled robot, a mechanical hand with photoelectric touch sensors

for grasping nuclear materials.

Minsky collaborated with Papert to develop semi-independent

programs that could interact with one another to address increasingly complex

challenges in computer vision and manipulation.

Minsky and Papert combined their nonhierarchical management

techniques into a natural intelligence hypothesis known as the Society of Mind.

Intelligence, according to this view, is an emergent feature

that results from tiny interactions between programs.

After studying various constructions, the MIT AI Group

trained a computer-controlled robot to build structures out of children's

blocks by 1970.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the blocks-manipulating

robot and the Society of Mind hypothesis evolved.

Minsky finally released The Society of Mind (1986), a model

for the creation of intelligence through individual mental actors and their

interactions, rather than any fundamental principle or universal technique.

He discussed consciousness, self, free will, memory, genius,

language, memory, brainstorming, learning, and many other themes in the book,

which is made up of 270 unique articles.

Agents, according to Minsky, do not require their own mind,

thinking, or feeling abilities.

They are not intelligent.

However, when they work together as a civilization, they

develop what we call human intellect.

To put it another way, understanding how to achieve any

certain goal requires the collaboration of various agents.

Agents are required by Minsky's robot constructor to see,

move, locate, grip, and balance blocks.

"I'd like to believe that this effort provided us

insights into what goes on within specific sections of children's brains when

they learn to 'play' with basic toys," he wrote (Minsky 1986, 29).

Minsky speculated that there may be over a hundred agents

collaborating to create what we call mind.

In the book Emotion Machine, he expanded on his views on

Society of Mind (2006).

He argued that emotions are not a separate kind of reasoning

in this section.

Rather, they reflect different ways of thinking about

various sorts of challenges that people face in the real world.

According to Minsky, the mind changes between different

modes of thought, thinks on several levels, finds various ways to represent

things, and constructs numerous models of ourselves.

Minsky remarked on a broad variety of popular and

significant subjects linked to artificial intelligence and robotics in his

final years via his books and interviews.

The Turing Option (1992), a book created by Minsky in

partnership with science fiction novelist Harry Harrison, is set in the year

2023 and deals with issues of artificial intelligence.

In a 1994 article for Scientific American headlined

"Will Robots Inherit the Earth?" he said, "Yes, but they will be

our children" (Minsky 1994, 113).

Minsky once suggested that a superintelligent AI may one day

spark a Riemann Hypothesis Catastrophe, in which an agent charged with

answering the hypothesis seizes control of the whole planet's resources in

order to obtain even more supercomputing power.

He didn't think this was a plausible scenario.

Humans could be able to converse with intelligent alien life

forms, according to Minsky.

They'd think like humans because they'd be constrained by

the same "space, time, and material constraints" (Minsky 1987, 117).

Minsky was also a critic of the Loebner Prize, the world's

oldest Turing Test-like competition, claiming that it is detrimental to

artificial intelligence research.

To anybody who could halt Hugh Loebner's yearly competition,

he offered his own Minsky Loebner Prize Revocation Prize.

Both Minsky and Loebner died in 2016, yet the Loebner Prize

competition is still going on.

Minsky was also responsible for the development of the

confocal microscope (1957) and the head-mounted display (HMD) (1963).

He was awarded the Turing Award in 1969, the Japan Prize in 1990, and the Benjamin Franklin Medal in 1991. (2001). Daniel Bobrow (operating systems), K. Eric Drexler (molecular nanotechnology), Carl Hewitt (mathematics and philosophy of logic), Danny Hillis (parallel computing), Benjamin Kuipers (qualitative simulation), Ivan Sutherland (computer graphics), and Patrick Winston (computer graphics) were among Minsky's doctoral students (who succeeded Minsky as director of the MIT AI Lab).

Find Jai on Twitter | LinkedIn | Instagram

You may also want to read more about Artificial Intelligence here.

See also:

AI Winter; Chatbots and Loebner Prize; Dartmouth AI Conference; 2001: A Space Odyssey.

References & Further Reading:

Bernstein, Jeremy. 1981. “Marvin Minsky’s Vision of the Future.” New Yorker, December 7, 1981. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1981/12/14/a-i.

Minsky, Marvin. 1986. The Society of Mind. London: Picador.

Minsky, Marvin. 1987. “Why Intelligent Aliens Will Be Intelligible.” In Extraterrestrials: Science and Alien Intelligence, edited by Edward Regis, 117–28. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Minsky, Marvin. 1994. “Will Robots Inherit the Earth?” Scientific American 271, no. 4 (October): 108–13.

Minsky, Marvin. 2006. The Emotion Machine. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Minsky, Marvin, and Seymour Papert. 1969. Perceptrons: An Introduction to Computational Geometry. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Singh, Push. 2003. “Examining the Society of Mind.” Computing and Informatics 22, no. 6: 521–43.