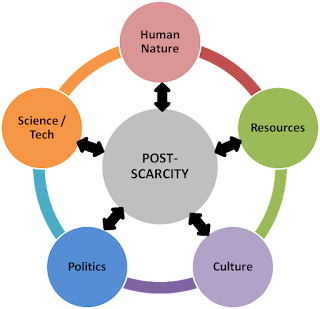

Post-scarcity is a controversial idea about a

future global economy in which a radical abundance of products generated at low

cost utilizing sophisticated technologies replaces conventional human labor and

wage payment.

Engineers, futurists, and science fiction writers have

proposed a wide range of alternative economic and social structures for a

post-scarcity world.

Typically, these models rely on hyperconnected systems of

artificial intelligence, robotics, and molecular nanofactories and

manufacturing to overcome scarcity—an pervasive aspect of current capitalist

economy.

In many scenarios, sustainable energy comes from nuclear

fusion power plants or solar farms, while materials come from asteroids mined

by self-replicating smart robots.

Other post-industrial conceptions of socioeconomic

structure, such as the information society, knowledge economy, imagination age,

techno-utopia, singularitarianism, and nanosocialism, exist alongside

post-scarcity as a material and metaphorical term.

Experts and futurists have proposed a broad variety of dates

for the transition from a post-industrial capitalist economy to a post-scarcity

economy, ranging from the 2020s to the 2070s and beyond.

The "Fragment on Machines" unearthed in Karl

Marx's (1818–1883) unpublished notebooks is a predecessor of post-scarcity

economic theory.

Advances in machine automation, according to Marx, would

diminish manual work, cause capitalism to collapse, and usher in a socialist

(and ultimately communist) economic system marked by leisure, artistic and

scientific inventiveness, and material prosperity.

The modern concept of a post-scarcity economy can be traced

back to political economist Louis Kelso's (1913–1991) mid-twentieth-century

descriptions of conditions in which automation causes a near-zero drop in the

price of goods, personal income becomes superfluous, and self-sufficiency and

perpetual vacations become commonplace.

Kelso advocated for more equitable allocation of social and

political power through democratizing capital ownership distribution.

This is significant because in a post-scarcity economy,

individuals who hold capital will also own the technologies that allow for

plenty.

For example, entrepreneur Mark Cuban has predicted that the

first trillionaire would be in the artificial intelligence industry.

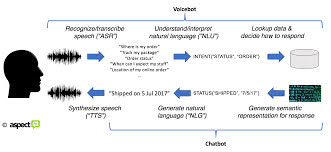

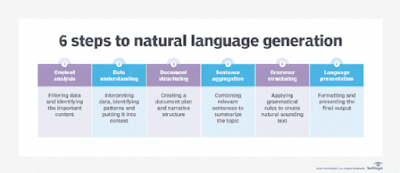

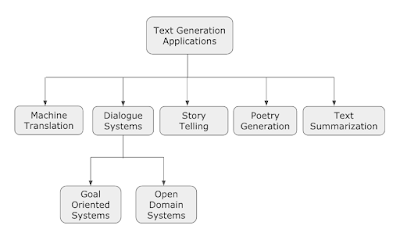

Artificial intelligence serves as a constant and pervasive

analytics platform in the post-scarcity economy, harnessing machine productivity.

AI directs the robots and other machinery that transform raw

materials into completed products and run other critical services like

transportation, education, health care, and water supply.

At practically every work-related endeavor, field of industry,

and line of business, smart technology ultimately outperform humans.

Traditional professions and employment marketplaces are

becoming extinct.

The void created by the disappearance of wages and salaries

is filled by a government-sponsored universal basic income or guaranteed

minimum income.

The outcomes of such a situation may be utopian, dystopian,

or somewhere in the between.

Post-scarcity AI may be able to meet practically all human

needs and desires, freeing individuals up to pursue creative endeavors,

spiritual contemplation, hedonistic urges, and the pursuit of joy.

Alternatively, the aftermath of an AI takeover might be a

worldwide disaster in which all of the earth's basic resources are swiftly

consumed by self-replicating robots that multiply exponentially.

K. Eric Drexler (1955–), a pioneer in nanotechnology, coined

the phrase "gray goo event" to describe this kind of worst-case

ecological calamity.

An intermediate result might entail major changes in certain

economic areas but not others.

According to Andrew Ware of the University of Cambridge's

Centre for the Study of Existential Risk (CSER), AI will have a huge impact on

agriculture, altering soil and crop management, weed control, and planting and

harvesting (Ware 2018).

According to a survey of data compiled by the McKinsey

Global Institute, managerial, professional, and administrative tasks are among

the most difficult for an AI to handle—particularly in the helping professions

of health care and education (Chui et al. 2016).

Science fiction writers fantasize of a society when clever

machines churn out most material items for pennies on the dollar.

The matter duplicator in Murray Leinster's 1935 short tale

"The Fourth Dimensional Demonstrator" is an early example.

Leinster invents a duplicator-unduplayer that takes use of

the fact that the four-dimensional world (the three-dimensional physical

universe plus time) has some thickness.

The technology snatches fragments from the past and

transports them to the present.

Pete Davidson, who inherits the equipment from his inventor

uncle, uses it to reproduce a banknote put on the machine's platform.

The note stays when the button is pressed, but it is joined

by a replica of the note that existed seconds before the button was pressed.

Because the duplicate of the bill has the same serial

number, this may be determined.

Davidson uses the equipment to comic effect, duplicating

gold and then (accidentally) removing pet kangaroos, girlfriends, and police

officers from the fourth dimension.

With Folded Hands (1947) by Jack Williamson introduces the

Humanoids, a species of thinking black mechanicals who serve as domestics,

doing all of humankind's labor and adhering to their responsibility to

"serve and obey, and defend men from danger" (Williamson 1947, 7).

The robots seem to be well-intentioned, but they are slowly

removing all meaningful work from human humans in the village of Two Rivers.

The Humanoids give every convenience, but they also

eliminate any human risks, such as sports and alcohol, as well as any

motivation to accomplish things for themselves.

Home doorknobs are even removed by the mechanicals since people

should not have to make their own entries and exits.

People get anxious, afraid, and eventually bored.

For a century or more, science fiction writers have

envisaged economies joined together by post-scarcity and vast possibility.

When an extraterrestrial species secretly dumps a score of

matter duplicating machines on the planet, Ralph Williams' novella

"Business as Usual, During Alterations" (1958) investigates human

greed.

Each of the electrical machines, which have two metal pans

and a single red button, is the same.

"A press of the button fulfills your heart's

wish," reads a written caution on the duplicator.

It's also a chip embedded in human society's underpinnings.

It will be brought down by a few billion of these chips.

It's all up to you" (Williams 1968, 288).

Williams' narrative is set on the day the gadget emerges,

and it takes place in Brown's Department Store.

John Thomas, the manager, has exceptional vision,

understanding that the robots would utterly disrupt retail by eliminating both

scarcity and the value of items.

Rather of attempting to create artificial scarcity, Thomas

comes up with the concept of duplicating the duplicators and selling them on

credit to clients.

He also reorients the business to offer low-cost items that

can be duplicated in the pan.

Instead of testing humanity's selfishness, the

extraterrestrial species is presented with an abundant economy based on a

completely different model of production and distribution, where distinctive

and varied items are valued above uniform ones.

The phrase "Business as Usual, During Changes"

appears on occasion in basic economics course curricula.

In the end, William's story is similar to the long-tail

distributions of more specialist products and services described by authors on

the economic and social implications of high technology like Clay Shirky, Chris

Anderson, and Erik Brynjolfsson.

In 1964, Leinster returned with The Duplicators, a short

book. In this novel, the planet Sord Three's human civilization

has lost much of its technological prowess, as well as all electrical devices,

and has devolved into a rough approximation of feudal society.

Humans are only able to utilize their so-called dupliers to

produce necessary items like clothing and silverware.

Dupliers have hoppers where vegetable matter is deposited

and raw ingredients are harvested to create other, more complicated

commodities, but they pale in comparison to the originals.

One of the characters speculates that this may be due to a

missing ingredient or components in the feedstock.

It's also self-evident that when poor samples are repeated,

the duplicates will be weaker.

The heavy weight of numerous, but poor products bears down

on the whole community.

Electronics, for example, are utterly gone since machines

cannot recreate them.

When the story's protagonist, Link Denham, arrives on the

planet in unduplicated attire, they are taken aback.

"And dupliers released to mankind would amount to

treason," Denham speculates in the story, referring to the potential

untold wealth as well as the collapse of human civilization throughout the

galaxy if the dupliers become known and widely used off the planet: "And

dupliers released to mankind would amount to treason." If a gadget exists

that can accomplish every kind of job that the world requires, people who are

the first to own it are wealthy beyond their wildest dreams.

However, pride will turn wealth into a marketable narcotic.

Men will no longer work since their services are no longer

required.

Men will go hungry because there is no longer any need to

feed them" (Leinster 1964, 66–67).

Native "uffts," an intelligent pig-like species

trapped in slavery as servants, share the planet alongside humans.

The uffts are adept at gathering the raw materials needed by

the dupliers, but they don't have direct access to them.

They are completely reliant on humans for some of the

commodities they barter for, particularly beer, which they like.

Link Denham utilizes his mechanical skill to unlock the

secrets of the dupliers, allowing them to make high-value blades and other

weapons, and finally establishes himself as a kind of Connecticut Yankee in King

Arthur's Court.

Humans and uffts equally devastate the environment as they

feed more and more vegetable stuff into the dupliers to manufacture the

enhanced products, too stupid to take full use of Denham's rediscovery of the

appropriate recipes and proportions.

This bothers Denham, who had hoped that the machines could

be used to reintroduce modern agricultural implements to the planet, after

which they could be used solely for repairing and creating new electronic goods

in a new economic system he devised, dubbed "Householders for the

Restoration of the Good Old Days" by the local humans.

The good times are ended soon enough, as humans plan the

re-subjugation of the native uffts, prompting them to form a Ufftian Army of

Liberation.

Link Denham deflects the uffts at first with generous

helpings of bureaucratic bureaucracy, then liberates them by developing

beer-brewing equipment privately, ending their need on the human trade.

The Diamond Age is a Hugo Award-winning bildungsroman about

a society governed by nanotechnology and artificial intelligence, written by

Neal Stephenson in 1995.

The economy is based on a system of public matter compilers,

which are essentially molecular assemblers that act as fabricating devices and

function similarly to K. Eric Drexler's proposed nanomachines in Engines of Creation

(1986), which "guide chemical reactions by positioning reactive molecules

with atomic precision" (Drexler 1986, 38).

All individuals are free to utilize the matter compilers,

and raw materials and energy are given from the Source, a massive hole in the

earth, through the Feed, a centralized utility system.

"Whenever Nell's clothing were too small, Harv would

toss them in the deke bin and have the M.C. sew new ones for her."

Tequila would use the M.C. to create Nell a beautiful outfit with lace and ribbons if

they were going somewhere where they would see other parents with other

girls" (Stephenson 1995, 53).

Nancy Kress's short tale "Nano Comes to Clifford

Falls" (2006) examines the societal consequences of nanotechnology, which

gives every citizen's desire.

It recycles the old but dismal cliche of humans becoming

lazy and complacent when presented with technology solutions, but this time it

adds the twist that males in a society suddenly free of poverty are at risk of

losing their morals.

"Printcrime" (2006), a very short article initially

published in the magazine Nature by Cory Doctorow, who, by no coincidence,

releases free works under a liberal Creative Commons license.

The tale follows Lanie, an eighteen-year-old girl who

remembers the day ten years ago when the cops arrived to her father's

printer-duplicator, which he was employing to illegally create pricey,

artificially scarce drugs.

One of his customers basically "shopped" him,

alerting him of his activities.

Lanie's father had just been released from jail in the

second part of the narrative.

He's immediately inquiring where he can "get a printer

and some goop," acknowledging that printing "rubbish" in the

past was a mistake, but then whispers to Lanie, "I'm going to produce more

printers." There are a lot more printers.

There's one for everyone. That is deserving of incarceration.

That's worth a lot." Makers (2009), also by Cory

Doctorow, is about a do-it-yourself (DIY) maker subculture that hacks

technology, financial systems, and living arrangements to "find means of

remaining alive and happy even while the economy is going down the

toilet," as the author puts it (Doctorow 2009).

The impact of a contraband carbon nanotube printing machine

on the world's culture and economy is the premise of pioneering cyberpunk author

Bruce Sterling's novella Kiosk (2008).

Boroslav, the protagonist, is a popup commercial kiosk

operator in a poor world nation, most likely a future Serbia.

He begins by obtaining a standard quick prototyping 3D

printer.

Children buy cards to program the gadget and manufacture

waxy, nondurable toys or inexpensive jewelry.

Boroslav eventually ends himself in the hands of a smuggled

fabricator who can create indestructible objects in just one hue.

Those who return their items to be recycled into fresh raw

material are granted refunds.

He is later discovered to be in possession of a gadget

without the necessary intellectual property license, and in exchange for his

release, he offers to share the device with the government for research

purposes.

However, before handing up the gadget, he uses the

fabricator to duplicate it and conceal it in the jungles until the moment is

right for a revolution.

The expansive techno-utopian Culture series of books

(1987–2012) by author Iain M. Banks involves superintelligences living alongside humans

and aliens in a galactic civilization marked by space socialism and a

post-scarcity economy.

Minds, benign artificial intelligences, manage the Culture

with the assistance of sentient drones.

The sentient living creatures in the novels do not work

since the Minds are superior and offer all the citizens need.

As the biological population indulges in hedonistic

indulgences and faces the meaning of life and fundamental ethical dilemmas in a

utilitarian cosmos, this reality precipitates all kinds of conflict.

~ Jai Krishna Ponnappan

Find Jai on Twitter | LinkedIn | Instagram

You may also want to read more about Artificial Intelligence here.

See also:

Ford, Martin; Technological Singularity; Workplace Automation.

References & Further Reading:

Aguilar-Millan, Stephen, Ann Feeney, Amy Oberg, and Elizabeth Rudd. 2010. “The Post-Scarcity World of 2050–2075.” Futurist 44, no. 1 (January–February): 34–40.

Bastani, Aaron. 2019. Fully Automated Luxury Communism. London: Verso.

Chase, Calum. 2016. The Economic Singularity: Artificial Intelligence and the Death of Capitalism. San Mateo, CA: Three Cs.

Chui, Michael, James Manyika, and Mehdi Miremadi. 2016. “Where Machines Could Replace Humans—And Where They Can’t (Yet).” McKinsey Quarterly, July 2016. http://pinguet.free.fr/wheremachines.pdf.

Doctorow, Cory. 2006. “Printcrime.” Nature 439 (January 11). https://www.nature.com/articles/439242a.

Doctorow, Cory. 2009. “Makers, My New Novel.” Boing Boing, October 28, 2009. https://boingboing.net/2009/10/28/makers-my-new-novel.html.

Drexler, K. Eric. 1986. Engines of Creation: The Coming Era of Nanotechnology. New York: Doubleday.

Kress, Nancy. 2006. “Nano Comes to Clifford Falls.” Nano Comes to Clifford Fall and Other Stories. Urbana, IL: Golden Gryphon Press.

Leinster, Murray. 1964. The Duplicators. New York: Ace Books.

Pistono, Federico. 2014. Robots Will Steal Your Job, But That’s OK: How to Survive the Economic Collapse and Be Happy. Lexington, KY: Createspace.

Saadia, Manu. 2016. Trekonomics: The Economics of Star Trek. San Francisco: Inkshares.

Stephenson, Neal. 1995. The Diamond Age: Or, a Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer. New York: Bantam Spectra.

Ware, Andrew. 2018. “Can Artificial Intelligence Alleviate Resource Scarcity?” Inquiry Journal 4 (Spring): n.p. https://core.ac.uk/reader/215540715.

Williams, Ralph. 1968. “Business as Usual, During Alterations.” In 100 Years of Science Fiction, edited by Damon Knight, 285–307. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Williamson, Jack. 1947. “With Folded Hands.” Astounding Science Fiction 39, no. 5 (July): 6–45.