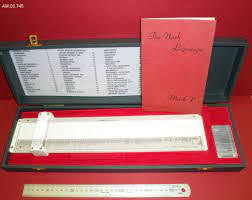

Firmin Nash, director of the South West London Mass X-Ray Service, devised the Group Symbol Associator, a slide rule-like device that enabled a clinician to correlate a patient's symptoms against 337 predefined symptom-disease complexes and establish a diagnosis in the early 1950s.

It resolves cognitive processes in automated medical

decision-making by using multi-key look-up from inverted files.

The Group Symbol Associator has been dubbed a

"cardboard brain" by Derek Robinson, a professor at the Ontario

College of Art & Design's Integrated Media Program.

Hugo De Santo Caro, a Dominican monk who finished his index

in 1247, used an inverted scriptural concordance similar to this one.

Marsden Blois, an artificial intelligence in medicine

professor at the University of California, San Francisco, rebuilt the Nash

device in software in the 1980s.

Blois' diagnostic aid RECONSIDER, which is based on the

Group Symbol Associator, performed as good as or better than other expert

systems, according to his own testing.

Nash dubbed the Group Symbol Associator the

"Logoscope" because it employed propositional calculus to analyze

different combinations of medical symptoms.

The Group Symbol Associator is one of the early efforts to

apply digital computers to diagnostic issues, in this instance by adapting an

analog instrument.

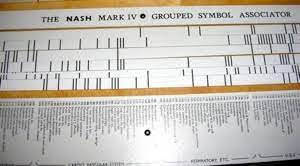

Along the margin of Nash's cardboard rule, disease groupings

chosen from mainstream textbooks on differential diagnosis are noted.

Each patient symptom or property has its own cardboard

symptom stick with lines opposing the locations of illnesses that share that

property.

There were a total of 82 sign and symptom sticks in the

Group Symbol Associator.

Sticks that correspond to the state of the patient are

chosen and entered into the rule.

Nash's slide rule is simply a matrix with illnesses as

columns and properties as rows.

Wherever qualities are predicted in each illness, a mark

(such as a "X") is inserted into the matrix.

Rows that describe symptoms that the patient does not have

are removed.

The most probable or "best match" diagnosis is

shown by columns with a mark in every cell.

When seen as a matrix, the Nash device reconstructs

information in the same manner as peek-a-boo card retrieval systems did in the

1940s to manage knowledge stores.

The Group Symbol Associator is similar to Leo J. Brannick's analog computer for medical diagnosis, Martin Lipkin and James Hardy's McBee punch card system for diagnosing hematological diseases, Keeve Brodman's Cornell Medical Index Health Questionnaire, Vladimir K.

Zworykin's symptom spectra analog computer, and other

"peek-a-boo" card systems and devices.

The challenge that these devices are trying to solve is

locating or mapping illnesses that are suited for the patient's mix of

standardized features or attributes (signs, symptoms, laboratory findings,

etc.).

Nash claimed to have condensed a physician's memory of

hundreds of pages of typical diagnostic tables to a little machine around a

yard long.

Nash claimed that his Group Symbol Associator obeyed the

"rule of mechanical experience conservation," which he coined.

"Will man crumble under the weight of the wealth of

experience he has to bear and pass on to the next generation if our books and

brains are reaching relative inadequacy?" he wrote.

I don't believe so.

Power equipment and labor-saving gadgets took on the

physical strain.

Now is the time to usher in the age of thought-saving

technologies" (Nash 1960b, 240).

Nash's equipment did more than just help him remember

things.

He asserted that the machine was involved in the diagnostic

procedure' logical analysis.

"Not only does the Group Symbol Associator represent

the final results of various diagnostic classificatory thoughts, but it also

displays the skeleton of the whole process as a simultaneous panorama of

spectral patterns that correlate with changing degrees of completeness,"

Nash said.

"For each diagnostic occasion, it creates a map or

pattern of the issue and functions as a physical jig to guide the mental

process" (Paycha 1959, 661).

On October 14, 1953, a patent application for the invention

was filed with the Patent Office in London.

At the 1958 Mechanization of Thought Processes Conference at

the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) in the Teddington region of London, Nash

conducted the first public demonstration of the Group Symbol Associator.

The NPL meeting in 1958 is notable for being just the second

to be held on the topic of artificial intelligence.

In the late 1950s, the Mark III Model of the Group Symbol

Associator became commercially available.

Nash hoped that when doctors were away from their offices

and books, they would bring Mark III with them.

"The GSA is tiny, affordable to create, ship, and

disseminate," Nash noted.

It is simple to use and does not need any maintenance.

Even in outposts, ships, and other places, a person might

have one" (Nash 1960b, 241).

Nash also published instances of xerography (dry

photocopying)-based "logoscopic photograms" that obtained the same

outcomes as his hardware device.

Medical Data Systems of Nottingham, England, produced the

Group Symbol Associator in large quantities.

Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical Company distributed the majority

of the Mark V devices in Japan.

In 1959, Nash's main opponent, François Paycha, a French

ophthalmologist, explained the practical limits of Nash's Group Symbol

Associator.

He pointed out that in the identification of corneal

diseases, where there are roughly 1,000 differentiable disorders and 2,000

separate indications and symptoms, such a gadget would become highly

cumbersome.

The instrument was examined in 1975 by R. W. Pain of the

Royal Adelaide Hospital in South Australia, who found it to be accurate in just

a quarter of instances.

You may also want to read more about Artificial Intelligence here.

See also:

Computer-Assisted Diagnosis.

Further Reading:

Eden, Murray. 1960. “Recapitulation of Conference.” IRE Transactions on Medical Electronics ME-7, no. 4 (October): 232–38.

Nash, F. A. 1954. “Differential Diagnosis: An Apparatus to Assist the Logical Faculties.” Lancet 1, no. 6817 (April 24): 874–75.

Nash, F. A. 1960a. “Diagnostic Reasoning and the Logoscope.” Lancet 2, no. 7166 (December 31): 1442–46.

Nash, F. A. 1960b. “The Mechanical Conservation of Experience, Especially in Medicine.” IRE Transactions on Medical Electronics ME-7, no. 4 (October): 240–43.

Pain, R. W. 1975. “Limitations of the Nash Logoscope or Diagnostic Slide Rule.” Medical Journal of Australia 2, no. 18: 714–15.

Paycha, François. 1959. “Medical Diagnosis and Cybernetics.” In Mechanisation of Thought Processes, vol. 2, 635–67. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office