Computational Creativity is a term used to

describe a kind of creativity that is based on Computer-generated art is

connected to computational creativity, although it is not reducible to it.

According to Margaret Boden, "CG-art" is an

artwork that "results from some computer program being allowed to operate

on its own, with zero input from the human artist" (Boden 2010, 141).

This definition is both severe and limiting, since it is

confined to the creation of "art works" as defined by human

observers.

Computational creativity, on the other hand, is a broader

phrase that encompasses a broader range of actions, equipment, and outputs.

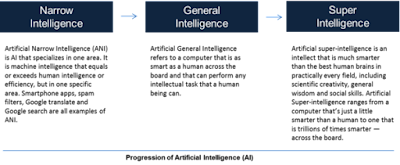

"Computational creativity is an area of Artificial

Intelligence (AI) study... where we construct and engage with computational systems

that produce products and ideas," said Simon Colton and Geraint A. Wiggins.

Those "artefacts and ideas" might be works of art,

as well as other things, discoveries, and/or performances (Colton and Wiggins

2012, 21).

Games, narrative, music composition and performance, and

visual arts are examples of computational creativity applications and

implementations.

Games and other cognitive skill competitions are often used

to evaluate and assess machine skills.

The fundamental criterion of machine intelligence, in fact,

was established via a game, which Alan Turing dubbed "The Game of

Imitation" (1950).

Since then, AI progress and accomplishment have been

monitored and evaluated via games and other human-machine contests.

Chess has had a special status and privileged position among

all the games in which computers have been involved, to the point where critics

such as Douglas Hofstadter (1979, 674) and Hubert Dreyfus (1992) confidently

asserted that championship-level AI chess would forever remain out of reach and

unattainable.

After beating Garry Kasparov in 1997, IBM's Deep Blue

modified the game's rules.

But chess was just the start.

In 2015, AlphaGo, a Go-playing algorithm built by Google

DeepMind, defeated Lee Sedol, one of the most famous human players of this notoriously

tough board game, in four out of five games.

Human observers, including as Fan Hui (2016), have praised

AlphaGo's nimble play as "beautiful," "intuitive," and

"innovative." 'Automated Insights' is a service provided by Automated

Insights Natural Language Generation (NLG) techniques such as Wordsmith and

Narrative Science's Quill are used to create human-readable tales from

machine-readable data.

Unlike basic news aggregators or template NLG systems, these

computers "write" (or "produce," as the case may be) unique

tales that are almost indistinguishable from human-created material in many

cases.

Christer Clerwall, for example, performed a small-scale

research in 2014 in which human test subjects were asked to assess news pieces

written by Wordsmith and a professional writer from the Los Angeles Times.

The study's findings reveal that, although

software-generated information is often seen as descriptive and dull, it is

also regarded as more impartial and trustworthy (Clerwall 2014, 519).

"Within 10 years, a digital computer would produce

music regarded by critics as holding great artistic merit," Herbert Simon

and Allen Newell predicted in their famous article "Heuristic Problem

Solving" (1958). (Simon and Newell 1958, 7).

This prediction has come true.

Experiments in Musical Intelligence (EMI, or

"Emmy") by David Cope is one of the most well-known works in the

subject of "algorithmic composition."

Emmy is a computer-based

algorithmic composer capable of analyzing existing musical compositions,

rearranging their fundamental components, and then creating new, unique scores

that sound like and, in some circumstances, are indistinguishable from Mozart,

Bach, and Chopin's iconic masterpieces (Cope 2001).

There are robotic systems in music performance, such as

Shimon, a marimba-playing jazz-bot from Georgia Tech University, that can not

only improvise with human musicians in real time, but also "is designed to

create meaningful and inspiring musical interactions with humans, leading to

novel musical experiences and outcomes" (Hoffman and Weinberg 2011).

Cope's method, which he refers to as

"recombinacy," is not restricted to music.

It may be used and applied to any creative technique in

which new works are created by reorganizing or recombining a set of finite

parts, such as the alphabet's twenty-six letters, the musical scale's twelve

tones, the human eye's sixteen million colors, and so on.

As a result, other creative undertakings, like as painting,

have adopted similar computational creativity method.

The Painting Fool is an automated painter created by Simon

Colton that seeks to be "considered seriously as a creative artist in its

own right" (Colton 2012, 16).

To far, the algorithm has generated thousands of

"original" artworks, which have been shown in both online and

physical art exhibitions.

Obvious, a Paris-based collaboration comprised of the

artists Hugo Caselles-Dupré, Pierre Fautrel, and Gauthier Vernie, uses a

generative adversarial network (GAN) to create portraits of a fictitious family

(the Belamys) in the manner of the European masters.

Christies auctioned one of these pictures, "Portrait of

Edmond Belamy," for $432,500 in October 2018.

Designing ostensibly creative systems instantly runs into

semantic and conceptual issues.

Creativity is an enigmatic phenomena that is difficult to

pinpoint or quantify.

Are these programs, algorithms, and systems really "creative,"

or are they merely a sort of "imitation," as some detractors have

labeled them? This issue is similar to John Searle's (1984, 32–38) Chinese Room

thought experiment, which aimed to highlight the distinction between genuine

cognitive activity, such as creative expression, and simple simulation or

imitation.

Researchers in the field of computational creativity have

introduced and operationalized a rather specific formulation to characterize

their efforts: "The philosophy, science, and engineering of computational

systems that, by taking on specific responsibilities, exhibit behaviors that

unbiased observers would deem creative" (Colton and Wig gins 2012, 21).

The key word in this description is

"responsibility."

"The term responsibilities highlights the

difference between the systems we build and creativity support tools studied in

the HCI [human-computer interaction] community and embedded in tools like

Adobe's Photoshop, to which most observers would probably not attribute

creative intent or behavior," Colton and Wiggins explain (Colton and

Wiggins 2012, 21).

"The program is only a tool to improve human

creativity" (Colton 2012, 3–4) using a software application like

Photoshop; it is an instrument utilized by a human artist who is and remains responsible

for the creative choices and output created by the instrument.

Computational creativity research, on the other hand,

"seeks to develop software that is creative in and of itself" (Colton

2012, 4).

On the one hand, one might react as we have in the past,

dismissing contemporary technological advancements as simply another instrument

or tool of human action—or what technology philosophers such as Martin

Heidegger (1977) and Andrew Feenberg (1991) refer to as "the instrumental

theory of technology."

This is, in fact, the explanation supplied by David

Cope in his own appraisal of his work's influence and relevance.

Emmy and other algorithmic composition systems, according to

Cope, do not compete with or threaten to replace human composition.

They are just instruments used in and for musical creation.

"Computers represent just instruments with which we

stretch our ideas and bodies," writes Cope.

Computers, programs, and the data utilized to generate their

output were all developed by humanity.

Our algorithms make music that is just as much ours as music

made by our greatest human inspirations" (Cope 2001, 139).

According to Cope, no matter how much algorithmic mediation

is invented and used, the musical composition generated by these advanced digital

tools is ultimately the responsibility of the human person.

The similar argument may be made for other supposedly

creative programs, such as AlphaGo, a Go-playing algorithm, or The Painting

Fool, a painting software.

When AlphaGo wins a big tournament or The Painting Fool

creates a spectacular piece of visual art that is presented in a gallery, there

is still a human person (or individuals) who is (or can reply or answer for)

what has been created, according to the argument.

The attribution lines may get more intricate and drawn out,

but there is always someone in a position of power behind the scenes, it might

be claimed.

In circumstances where efforts have been made to transfer

responsibility to the computer, evidence of this already exists.

Consider AlphaGo's game-winning move 37 versus Lee Sedol in

game two.

If someone wants to learn more about the move and its

significance, AlphaGo is the one to ask.

The algorithm, on the other hand, will remain silent.

In actuality, it was up to the human programmers and

spectators to answer on AlphaGo's behalf and explain the importance and effect

of the move.

As a result, as Colton (2012) and Colton et al. (2015) point out, if the mission of computational creativity

is to succeed, the software will have to do more than create objects and

behaviors that humans interpret as creative output.

It must also take ownership of the task by accounting for

what it accomplished and how it did it.

"The software," Colton and Wiggins argue,

"should be available for questioning about its motivations, processes, and

products," eventually capable of not only generating titles for and

explanations and narratives about the work but also responding to questions by

engaging in critical dialogue with its audience (Colton and Wiggins 2012, 25). (Colton

et al. 2015, 15).

At the same time, these algorithmic incursions into what had

previously been a protected and solely human realm have created possibilities.

It's not only a question of whether computers, machine

learning algorithms, or other applications can or cannot be held accountable

for what they do or don't do; it's also a question of how we define, explain,

and define creative responsibility in the first place.

This suggests that there is a strong and weak component to

this endeavor, which Mohammad Majid al-Rifaie and Mark Bishop refer to as

strong and weak forms of computational creativity, reflecting Searle's initial

difference on AI initiatives (Majid al-Rifaie and Bishop 2015, 37).

The types of application development and demonstrations

presented by people and companies such as DeepMind, David Cope, and Simon

Colton are examples of the "strong" sort.

However, these efforts have a "weak AI" component

in that they simulate, operationalize, and stress test various

conceptualizations of artistic responsibility and creative expression,

resulting in critical and potentially insightful reevaluations of how we have

defined these concepts in our own thinking.

Nothing has made Douglas Hofstadter reexamine his own

thinking about thinking more than the endeavor to cope with and make sense of

David Cope's Emmy nomination (Hofstadter 2001, 38).

To put it another way, developing and experimenting with new

algorithmic capabilities does not necessarily detract from human beings and

what (hopefully) makes us unique, but it does provide new opportunities to be

more precise and scientific about these distinguishing characteristics and their

limits.

~ Jai Krishna Ponnappan

You may also want to read more about Artificial Intelligence here.

See also:

AARON; Automatic Film Editing; Deep Blue; Emily Howell; Generative Design; Generative Music and Algorithmic Composition.

Further Reading

Boden, Margaret. 2010. Creativity and Art: Three Roads to Surprise. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Clerwall, Christer. 2014. “Enter the Robot Journalist: Users’ Perceptions of Automated Content.” Journalism Practice 8, no. 5: 519–31.

Colton, Simon. 2012. “The Painting Fool: Stories from Building an Automated Painter.” In Computers and Creativity, edited by Jon McCormack and Mark d’Inverno, 3–38. Berlin: Springer Verlag.

Colton, Simon, Alison Pease, Joseph Corneli, Michael Cook, Rose Hepworth, and Dan Ventura. 2015. “Stakeholder Groups in Computational Creativity Research and Practice.” In Computational Creativity Research: Towards Creative Machines, edited by Tarek R. Besold, Marco Schorlemmer, and Alan Smaill, 3–36. Amsterdam: Atlantis Press.

Colton, Simon, and Geraint A. Wiggins. 2012. “Computational Creativity: The Final Frontier.” In Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications, vol. 242, edited by Luc De Raedt et al., 21–26. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Cope, David. 2001. Virtual Music: Computer Synthesis of Musical Style. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dreyfus, Hubert L. 1992. What Computers Still Can’t Do: A Critique of Artificial Reason. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Feenberg, Andrew. 1991. Critical Theory of Technology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Heidegger, Martin. 1977. The Question Concerning Technology, and Other Essays. Translated by William Lovitt. New York: Harper & Row.

Hoffman, Guy, and Gil Weinberg. 2011. “Interactive Improvisation with a Robotic Marimba Player.” Autonomous Robots 31, no. 2–3: 133–53.

Hofstadter, Douglas R. 1979. Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. New York: Basic Books.

Hofstadter, Douglas R. 2001. “Staring Emmy Straight in the Eye—And Doing My Best Not to Flinch.” In Virtual Music: Computer Synthesis of Musical Style, edited by David Cope, 33–82. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hui, Fan. 2016. “AlphaGo Games—English. DeepMind.” https://web.archive.org/web/20160912143957/

https://deepmind.com/research/alphago/alphago-games-english/.

Majid al-Rifaie, Mohammad, and Mark Bishop. 2015. “Weak and Strong Computational Creativity.” In Computational Creativity Research: Towards Creative Machines, edited by Tarek R. Besold, Marco Schorlemmer, and Alan Smaill, 37–50. Amsterdam: Atlantis Press.

Searle, John. 1984. Mind, Brains and Science. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.